Menopause vs. manopause – are they equivalent?

The menopause marks one of the biggest natural shifts in hormones for women and can bring with it a number of unpleasant symptoms. But is there a testosterone-based equivalent in men?

Hormones: The Inside Story

Episode 10 – Menopause vs. manopause – are they equivalent?

This is Hormones: The Inside Story - the podcast from the Society for Endocrinology where we look at the tiny things inside us pulling the strings

This time, we’re taking a look at what’s probably the biggest natural shift in human hormones outside of puberty: and that is the menopause. Despite this change occurring in up to half of the population, menopause is still a taboo and desperately under-researched subject.

And what about the other half of the population? Is there really a 'manopause' caused by plummeting male hormones, or is it a buzzword invented to prop up a billion dollar testosterone industry?

I’m Georgia Mills, and in this episode we’re asking what’s going on with our sex hormones as we age - and why does it matter?

Just a note before we get going. We recognise that people’s gender identities don't always match up with their birth sex, and there’s a range of genetic and hormonal conditions that affect reproductive health, often with very little research behind them, so no experience we discuss will be universal.

Let’s start with our basic definition of the menopause

Annice: Menopause literally means periods stopping so many periods and pause means stop, and the menopause is sort of defined by when a woman's eggs run out.

Georgia: This is Dr Annice Mukherjee, a consultant endocrinologist based in Manchester

Annice: So every baby girl is born with a finite number of eggs. And when she reaches puberty, she starts to release eggs on a monthly basis and that's what causes the monthly period cycle. And that's what results in the eggs being released, which produces a woman's fertility. And an adult woman then releases an egg every month or almost every month provided she's healthy through to when her eggs run out. And for every woman that's slightly different. In the UK, the average age of the eggs running out in menopause is 51 years. And after the menopause, a woman is no longer fertile and her periods stop.

Georgia: While menopause by a certain age is an inevitability, some go into it early, due to genetics, underlying health conditions, or the result of medical interventions like cancer treatment. And technically, if you have never had periods for any reason, then you can’t have them stop. But for those who do, figuring out exactly when this happens can be tricky.

Annice: It’s not: you have regular periods right the way through to fifty one then the periods stop and there's no more periods. Quite often your periods stop, then they restart and they're more erratic and you might have two or three a year or five a year for a couple of years before they actually stop. So actually any single woman doesn't really know she's gone through the menopause until she's not had a period for 12 consecutive months. So it's almost a retrospective diagnosis, a hindsight diagnosis. So although it sounds simple, it's your last period. No one really knows when that last period is going to be until after the event.

Georgia: And what are the hormonal changes that happen over this period.

Annice: Let's go to before the menopause, we've got the premenopausal hormones that cycle every month and there's a number of different hormones, brain hormones and ovarian hormones that move up and down through the month to optimise the egg release at the mid-cycle for the fertility aspect. So we produce estrogen, testosterone, progesterone are the three main hormones that move around through that menstrual cycle. So, after the age of 45, many women will start to experience something we describe as perimenopause, where that nice, harmonious hormone cycle starts to misfire a little bit and doesn't work quite as smoothly. And that's again, because the number of eggs are starting to wane and they're going down. And if there's not as many eggs - sometimes, some months a women might not even release an egg and her periods can start to become less regular - and with that can come a number of symptoms which we describe as perimenopause, but the symptoms in menopause and perimenopause are very similar.

Georgia: This change brings with it a litany of symptoms that vary from person to person, as they first go through perimenopause and then into menopause.

Annice: Well, since I started doing endocrinology, there was a list of a handful of symptoms that everybody associated with menopause, so things like hot sweats, night sweats and hot flushes, mood swings, irritability, fatigue and joint aches. But actually, there are almost an infinite number of symptoms that are now described to be associated with menopause now. Everything from feeling as if you've got insects crawling over your body, which is something described as formication, which is a relatively rare symptom of menopause, through to sleep disturbance, which is very common, low mood. Brain fog is a term that a lot of people relate to, which is sort of in medical terms, we call it cognitive dysfunction, where your memory and your focus just go right out of sync and you can become more forgetful and that can be quite frightening. One in four women say about 25 percent of women will experience severe menopausal symptoms. Three in four will not. I would say I don't want people to think, gosh, this is never going to go away, because for the vast majority it does.

Georgia: But why does a drop in oestrogen result in so MANY different symptoms?

Annice looks at it like a synchronised swimming team.

You have your hormones working together in harmony, in balance through the first chunk of your adult life - until you hit perimenopause

Some swimmers stop fulfilling their roles properly - oestrogen, progesterone and testosterone decide they can’t be bothered - and suddenly all the other hormones are trying to compensate for the missing swimmers.

Annice: It's just like a big splashy mess for a while.

Georgia: This splashy mess confuses the brain and the body, and is what causes this vast variety of symptoms for women. Frustratingly, because it’s so variable, it can be hard to figure out exactly what’s happening to cause each symptom and develop effective interventions - although there has been one recent breakthrough.

Annice: Well, the hot flushes is an interesting one because some very, very clever researchers based in the UK at Imperial College London, they are neuroendocrine researchers, neuroscience researchers, have found a hormone which seems to trigger the mechanism for hot sweats and flushes and this amazing group from Imperial College London have actually developed a tablet treatment to treat that hormone problem that triggers hot sweats and flushes. And it's incredibly exciting stuff because these studies are quite advanced now and they've been tested in humans. Giving this tablet treatment reduces hot sweats and flushes, and it also improves sleep quality and mood. So it's an amazing discovery and very much a watch this space, because when we get that medication available, it's going to be a game changer for many women because it will take those symptoms away and it is directly targeting the mechanism in a very safe way.

Georgia: Wow. So, big deal.

Annice: Yeah, I mean, I think there's very few breakthroughs in medicine that really make a difference, and in endocrinology, you know, there are breakthroughs all the time, but, you know, real game changers like that, I think it's rare. So I think I'm very, very excited about when the next paper is coming out.

Georgia: And for most people with severe symptoms, hormone replacement therapy is an option. This helps you gradually drop levels more calmly - so our synchronised swimmers have more time to adjust to their new routine.

HRT has a somewhat checkered history. Initially, only oestrogen was given to people, but if you have a uterus - oestrogen on its own can cause cancer in the womb, so then it was given with progesterone.

But then in the 1990s, a major study came out, finding that there were some risks associated with long-term HRT.

Annice: The prescribing of HRT dropped by about 50 percent virtually overnight. And that was because they found an increased risk of breast cancer with HRT and an increased risk of cardiovascular and blood vessel type problems. Women became very fearful. The media said HRT is very dangerous and very few women were given HRT.

Georgia: Follow-up studies were able to pick apart what was happening.

Annice: So they looked in more detail and found the women who were coming to harm were those women who were older and left on treatment without really much monitoring for decades, and younger women really didn't seem to come to much harm at all because HRT, we know, is also really good for bones. And in younger women it's good for heart protection. So it's about individualizing care.

Georgia: So we still have loads to learn about menopause, what about the males? Although the idea of a ‘manopause’ does pop up in health columns and men’s magazines, what is it? And is it actually real?

Channa: My name's Dr Channa Jayasena. So I work at Imperial College London as a reproductive and phrenologists with a special interest in fertility and sex hormones.

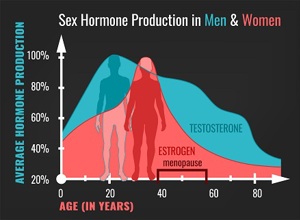

So in men, rather than a sudden drop in activity of the reproductive system, the testes produce about one percent less testosterone year on year from about the age of 40 so there's a gradual decline. And also, unlike women, there is far from an inevitability that men will ever require testosterone. In fact, most never do. Only a minority of men will have a reduction in testosterone with age that ever requires medical treatment.

Georgia: So this decline in testosterone is a gradual one, less of a hormonal cliff you can stumble off, but a gentle slope. This is a natural part of aging, but a few things can accelerate it.

Channa: So first of all, we think that the hypothalamus in the brain, which regulates the testes and ovaries, can naturally reduce activity with age. Secondly, the testes do as well. So bits of the body wear down. But it's also important to realise that older men are more likely to be on medications and have medical problems, things such as obesity or heart problems or high blood pressure, which also each add up to reduce testosterone. So in general, the less healthy you are, the lower testosterone you have. And we know that in general, someone aged 80 will have a lower level of health on average than someone who's age 20.

So the symptoms of having low testosterone can be very profound and impact quality of life. The most obvious symptoms are sexual: low libido, inability to have erections when you normally would, are the hallmarks of testosterone deficiency. But it can also affect mood, so increase depression risk, but also impair broad quality of life and also impair cognition, so your ability to concentrate and think properly.

Georgia: They sound they sound like they're not a million miles away from the symptoms described for menopause, especially the sort of brain fog and sort of the tiredness angle.

Channa: You're right, when you put it like that, you almost persuade me. Yes, you are right, there are many, many similarities. And in fact, with extreme testosterone deficiency, you can also get flushes, just as you would in menopause.

Georgia: If oestrogen and progesterone can help with some of the symptoms of menopause, can testosterone supplements help with this so-called 'manopause?

Channa: I think there are some who really think that you should try to supplement everyone with low testosterone because it's like the elixir of life. You will make these men younger, rejuvenate them. And then there are others who say, well, studies show that if you give testosterone to such men, if they don't start off with symptoms such as erectile dysfunction or libido, if they're just well, well, what are you really doing for them? And is it safe? Because if you give anything that raises testosterone or oestrogen, then there are small but significant risks of blood clots and changes to cholesterol levels, which are minute but if you start giving them to people who don't need it, those minor changes become important.

Georgia: Right. And is there an element here and you said this elixir of life, people promising the world and, you know, forever young, if you just take this pill and age just will stop happening.

Channa: Yeah, I think it is. And it's unfortunate because I think there are lots of people out there who want to believe this. And if you promise them these, then there will be people who come forward and pay for it. And I think this is more of a trend in North America. But of course, we have the Internet and these trends will spread worldwide. So there's no doubt that if a man took testosterone, you would increase your musculature as well. Something i haven’t really focused on, but that in a way is rejuvenating isn’t it, because you could have a body of someone much younger, but that sounds to me like anabolic steroid use, which is illegal. So there’s a very gray moral area here of what is acceptable and right. So the whole concept of testosterone and testosterone deficiency plugs into the male, you know, self, you know, sense of self identity and masculinity. So I personally don't think that we should be giving it merely for cosmetic reasons. I think we should. It is a medicinal product and we should be giving it that way. However, I think it's important to have this public debate about what the role of hormones is in society.

Promises of eternal youth and masculinity in a pill, have of course lead to some blatant exploitation and profiteering.

Channa: Here have been stories in America, but I'm sure that some of this would apply all over the world. There was an audit looking at testosterone prescriptions in the not too distant past in America, and they found that in many cases, levels of testosterone weren't even measured. So the men who were coming in with very vague. Symptoms of tiredness, which could be due to anything, were simply given testosterone, which should only be done if they have a low level of testosterone. So that's clearly inappropriate and dangerous and can risk very serious cardiovascular effects. And I am concerned about this growth in what we call lifestyle clinics. And this has been propagated in the States, where you give growth hormone, thyroid hormone testosterone in a very slapdash way. And all of these hormones stimulate people, stimulate the body, stimulate the metabolism in a way of trying to keep people young. Who knows what that's doing to your health?

Georgia: And I guess also, especially in America, it's not cheap to get things there.

Channa: Yeah, this is a multibillion dollar business, and I think we need to support those who need it. And I think the tragedy is that stories like that make people, clinicians who are sensible, cautious and prevent them from prescribing testosterone to the people who need it. And what we need is a middle ground where people who need it get it. And those who don't, don’t.

Basically, implying a big fall in testosterone is some biological inevitability, the same way the menopause is, isn’t a great idea

Channa: My personal view is that it's unhelpful to call things menopause simply because it gives the potential for people to misunderstand that it's inevitable. However as we’ve discussed there are elements that are similar, so if it helps to conceptualise what’s happening to your body, then there is merit in it.

Georgia: With both menopause and manopause - Sorry Channa, I won’t use that word again - there is a decline in sex hormones. The resulting physical and mental changes are also wrapped up in our identities, which can leave people vulnerable to discrimination and susceptible to miracle cures.

As Andrea Ford, an anthropologist at the University of Edinburgh, explains, the stories we tell ourselves about our hormones can have a real impact on our actual health and the way society treats us as we age, especially according to our gender.

Andrea: Up until the 18th century, the sexes were not seen as opposites or even different: female was an inferior version of the male. So they were actually the same thing with interchangeable parts. In the 18th century, they started being seen as opposites with women's physiology, making them passive and weak, and men's physiology making them active and strong. And not coincidentally, this was happening when there were a lot of political debates about women's rights and abilities. So you have the French and American revolutions happening at this time, the idea of democracy and who gets to participate in voting and the way that bodies were conceptualised was also really changing and very much influenced by and influencing the political accounts of the time. And then in the early 20th century, the sort of essence of womanhood changed from being an organ, the uterus or the womb, to being chemicals: hormones. So rather than having this. So I guess hormones became seen as really foundational to gender very recently, just about a century.

Georgia: And I guess like just the word hormonal. It's very loaded in terms of gender.

Andrea: And so, of course, there are many hormones that are not gendered, that are not gendered culturally, and that function very similarly in male and female and non-binary bodies. But something like saying you're hormonal or she's hormonal, that is very loaded, as you say.

Georgia: Despite affecting so many people throughout history, menopause hasn’t exactly been studied thoroughly.

Andrea: Historically, menopause is more conspicuous by its absence than anything else in terms of both medical research and social science research.

Georgia: But recent anthropological research is shedding some light on it.

Andrea: A really cool anthropological study about menopause compares ageing in Japan with ageing in North America, and now menopause shows up really differently in both places. This is a study done by Margaret Locke. And it really shows how in North America, the idea that menopause is a pathology and in fact a pathology that affects the entirety of females is not present in Japan. So, of course, women in Japan stop menstruating at a certain point, but it's not understood as pathological, as something that needs to be fixed, as something that's primarily about hormonal shifts. It's not talked about in terms of deficiency. So it doesn't necessarily make sense to offer hormone replacement therapy, which is becoming more and more common in the US. And so the same physiological process can be given really different meanings in different cultural situations. So when you're thinking about something like workplace protections, it might make the most sense to have menopause categorised as a sort of disability like pregnancy or chronic pain or any number of other things that workplaces need to make accommodation for, and that might be really good for making workplaces fairer places to be. So that would be great. And you can take it a little bit deeper and question whether menopause should be considered a pathology at all. And then in a kind of academic sense, what does that say about the society that really values youth so much that ageing is a disease and that can be seen in more examples than menopause itself and values male bodies to such an extent that a completely healthy female physiological process is considered a disease. Those are more fundamental questions that anthropology could also help with.

Georgia: That's really interesting and that study about how menopause is viewed; does that come across in terms of the symptoms being different as well?

Andrea: It does. So women in the study reported far fewer hot flashes and like forgetfulness. So the actual symptoms were different, which you could say that this has to do with other potential dietary factors, things like that, that that's possible. That could be studied as well to sort of figure out the complexity that goes into what symptoms people experience. What’s really interesting about that study is that people thought about those struggles in those responsibilities to other people and changes of roles in community, periods stopping was a footnote, whereas in the west, periods stopping and hormones changing is front and centre, in Japan it’s almost inverted.

Georgia: I asked Andrea if she thought anthropology had any answers for how we should treat hormonal decline in general.

Andrea: What is starting to happen is people being able to articulate for themselves what the problem is. A big issue with hormonal problems, especially gendered ones related to women or people who aren't men, has been that there are lots of social and cultural ideas about what's wrong with this person. For example, endometriosis is a chronic pain condition related to menstruation: that has been for decades called the career woman's disease, so if you're a woman and you're doing something like a demanding career, you're going to get sick because your body is not capable of that. And this idea that it's a career woman's disease meant that it was only studied in wealthy white women. It was only found in wealthy white women. It certainly happens in other types of people, but it wasn't studied because it didn't fit in with the idea of who should have this and why it might be happening to people. People who have endometriosis today have a really hard time getting taken seriously. And so there's been really important studies done recently about how difficult it is for women to get taken seriously in medical spaces. And I think in terms of hormones specifically, taking people at their word is the right direction to move in.

Georgia: So, when we age our sex hormones are going to inevitably decline. In theory, this shouldn’t affect our identity or value as people, but it can be hard to believe when faced with a barrage of symptoms, adverts for hormone supplements, and the threat of medical or workplace discrimination. Every single person is different, and their hormones will tell a different story over their lifetime. Alas, there’s no pill that can keep us young forever, but perhaps it’s time for all of us to do more to build a society that respects and supports everyone, whatever their age, and whatever their hormones are up too.

Thanks to Channa Jayasena, Annice Mukherjee and Andrea Ford

This show was produced by me, Georgia Mills. Kat Arney is the executive producer and it was made by FIRST CREATE THE MEDIA. Thanks for listening, and goodbye.