Alternative names for Cushing’s disease

Cushing disease

What is Cushing’s disease?

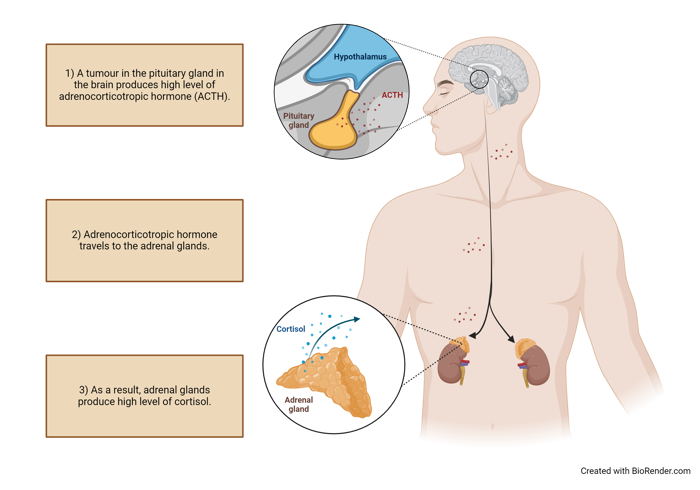

‘Cushing’s syndrome’ occurs when the body is exposed to high levels of cortisol for a prolonged period of time and can occur due to any cause of excess exposure to cortisol-like substances including synthetic corticosteroids. ‘Cushing’s disease’ is a specific type of Cushing’s syndrome, whereby a benign tumour of the pituitary gland stimulates the adrenal glands to produce too much cortisol.

What causes Cushing’s disease?

Cushing’s disease is caused by a tumour in the pituitary gland. This tumour produces high levels of a hormone called adrenocorticotropic hormone which, in turn, causes the adrenal glands to produce excessive amounts of the hormone, cortisol.

In most cases, the cause of the tumour cannot be identified. In a small number of cases, the pituitary tumour that causes Cushing’s disease is part of an inherited condition known as multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1.

What are the signs and symptoms of Cushing’s disease?

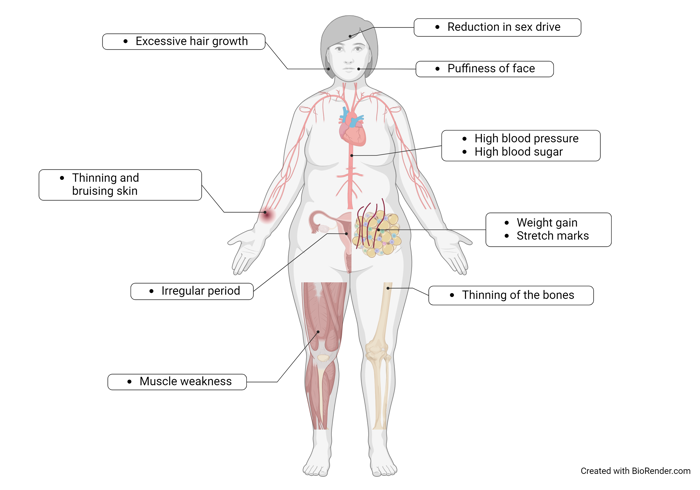

The signs and symptoms are weight gain (particularly around the midriff), puffiness of the face with a characteristic ‘flushed’ appearance, reduction in sex drive, irregular periods, thinning and bruising of the skin, stretch marks (particularly in the abdomen), muscle weakness (with wasting of the muscles in the arms and legs), excess hair growth (hirsutism), high blood pressure, high blood sugar (diabetes mellitus) and thinning of the bones increasing the risk of fractures (osteoporosis). An excess of cortisol can also cause low mood, anxiety, cognitive difficulties, and frequent or unusual infections. In children, Cushing’s disease leads to weight gain, a reduction in a child’s rate of growth, and can delay the onset of puberty.

How common is Cushing’s disease?

Cushing’s disease is very rare. One to three new patients per million are diagnosed each year, which means only approximately 60–180 new cases per year in the UK. It is more common in women and occasionally occurs in children. Cushing’s disease is very rare. One to three new patients per million are diagnosed each year, which means only approximately 60–180 new cases per year in the UK. It is more common in women and occasionally occurs in children.

Is Cushing’s disease inherited?

Most Cushing’s disease is not inherited. Less commonly, people who have inherited conditions such as multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 or familial isolated pituitary adenoma are at increased risk of Cushing’s disease. Most Cushing’s disease is not inherited. Less commonly, people who have inherited conditions such as multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 or familial isolated pituitary adenoma are at increased risk of Cushing’s disease.

How is Cushing’s disease diagnosed?

Outpatient tests include:

- A 24-hour urine collection - patients are asked to collect urine over a 24-hour period to measure cortisol levels, which are expected to be increased in Cushing’s syndrome.

- Dexamethasone suppression tests - these tests rely on the production of cortisol being suppressed when exposed to a strong steroid (dexamethasone) in a normal person without Cushing’s syndrome. However, a person with Cushing’s syndrome does not reduce their production of cortisol confirming that it is being abnormally over-secreted.

- One form is called the ‘overnight dexamethasone suppression test’, whereby patients are asked to take dexamethasone, a steroid tablet, followed by a blood test. Patients are typically asked to take a single dose of 1 mg between 11 p.m. and midnight, and then to return for a blood test at 9am the following morning. Alternatively, the ‘low-dose dexamethasone suppression test’ requires the individual to take 0.5 mg of dexamethasone every six hours for a period of 48 hours before returning for a blood test.

- Midnight Cortisol test – this may be done either as a blood test as an inpatient, or via collection of saliva as an outpatient taken at midnight. In healthy individuals, cortisol has a diurnal rhythm, i.e. it is high in the morning and low at midnight. In patients with Cushing’s syndrome, cortisol remains abnormally high at midnight.

- Inferior petrosal sinus sampling (IPSS) - this test involves placing a thin plastic tube into a vein in the groin area under local anaesthetic, which is threaded into the blood vessels near to the pituitary gland guided by an X-ray machine, and this is used to take blood samples to confirm the source of excess ACTH levels. If the excessive levels of ACTH are coming from the pituitary gland, this is consistent with Cushing’ Disease, whereas if ACTH levels are coming from elsewhere, this could be more consistent with Ectopic ACTH secretion as the cause of the Cushing’s syndrome.

- MRI of the pituitary gland - a dedicated scan of the pituitary gland using a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) machine can be used to identify a pituitary adenoma (a tumour that is not cancer) that is causing Cushing’s disease.

How is Cushing’s disease treated?

There are a number of different treatments for Cushing’s disease:

- Surgical removal of the pituitary tumour causing Cushing’s disease is the treatment of choice in most cases and is performed at specialist neurosurgical hospitals. The surgery is usually done through the nose and is successful in up to 80% of patients.

- Surgical removal of the adrenal glands, which sit on top of the kidneys can be performed at specialist hospitals. This operation is usually performed only if there is a particular reason for the pituitary tumour itself not being removed or if pituitary surgery has been unsuccessful in curing the disease. Adrenal removal can be done laparoscopically (key-hole surgery through small cuts in the skin).

- Medications to reduce cortisol overproduction or block cortisol action (e.g. metyrapone, ketoconazole, osilodrostat, and mifepristone), or to reduce adrenocorticotropic hormone overproduction by the pituitary tumour (e.g. pasireotide, cabergoline). Usually, medications are given only for a short time in order to prepare patients for surgery. These may also be used when surgery is unsuccessful or inappropriate.

- Radiotherapy to the pituitary gland. This is usually an outpatient therapy and is given when the patient is unable to have surgery. It is also sometimes used if pituitary surgery is unsuccessful in curing the disease. This treatment involves making a custom-fitted mask to allow the head to be positioned precisely under the radiotherapy machine. The treatment is either completed in a single day, or given over a period of several weeks in small daily doses.

Are there any side-effects to the treatment?

Possible side-effects of surgery include bleeding, infection or pain. After successful surgery to cure the Cushing’s disease, it is necessary for the cortisol hormone to be replaced, which is usually given as hydrocortisone tablets, taken two to three times a day. These may only be needed for a few months before normal pituitary and adrenal function returns, but occasionally have to be continued indefinitely.

Surgery of the pituitary gland may cause the other hormones made by the pituitary gland to fall in level and it may be necessary to replace these vital hormones with medications.

Medications to control cortisol or adrenocorticotropic hormone levels may have side effects, including abnormal liver function, increased blood sugar levels and abnormal heart rhythm. These can also interact with other medications (including over-the-counter remedies). Regular blood tests and clinical assessments are carried out to ensure there are no serious problems.

What are the longer-term implications of Cushing’s disease?

It is important that control of raised cortisol is achieved in order to prevent adverse health effects such as cardiovascular disease. Once the disease is cured, the changes due to excessive cortisol production will return to normal over the following weeks or months. The patient’s appearance will return, often rapidly, to normal, and muscle and bone strength will also improve.

Blood pressure and blood sugar will need to be watched and, if they remain raised, may need to be treated as in any other patient.

If the Cushing’s disease is cured, patients may need to continue taking hydrocortisone replacement tablets for life. If the body is unable to make its own cortisol in response to stressful situations such as illness, surgery and injury to the body, hydrocortisone may be needed in such situations to ensure that the body is able to cope.

Even once in remission, patients who have had Cushing’s disease for a prolonged period of time may have thin bones (osteoporosis) and weak muscles. Weight-bearing activity is important to improve both muscle and bone strength. If osteoporosis is present, this may require further medication to improve the strength of the bones and prevent fractures.

Even for patients who are considered to be cured, long-term follow-up with a specialist (endocrinologist) is required as there is a chance of relapse. Patients should discuss any concerns with a medical professional.