Alternative names for Cushing’s syndrome

Hypercortisolism; Cushing syndrome

What is Cushing’s syndrome?

Photo of stretch marks on a woman suffering from Cushing's syndrome.

Cushing’s syndrome is a disorder that occurs when the body is exposed to an excess of the hormone cortisol or similar synthetic versions. The hormone cortisol belongs to a group of hormones called steroids and regulates various biological pathways including stress. Cushing’s syndrome can occur either because:

- the body produces too much cortisol hormone by itself (known as ‘endogenous’ Cushing’s syndrome) or,

- a person takes large amounts of steroid medication to treat conditions such as asthma, rheumatoid arthritis or eczema. This is known as ‘exogenous’ Cushing’s syndrome.

What causes Cushing’s syndrome?

Cortisol is a steroid hormone produced by the adrenal glands, which sit on top of the kidneys. The adrenal glands are stimulated by a pituitary hormone called adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) to release cortisol into the bloodstream.

There are a number of causes of Cushing’s syndrome:

- The most common cause is steroid medication taken to treat conditions such as eczema, asthma or rheumatoid arthritis.

- A tumour of the pituitary gland that produces too much ACTH. Excess ACTH due to a pituitary tumour is called Cushing’s disease and although this is quite rare, it is the commonest cause of endogenous Cushing’s syndrome (when the body produces too much cortisol).

- Over activity of the adrenal gland (adrenal Cushing’s) causing excess cortisol production. This is less common than Cushing’s disease.

- Non-pituitary tumours that produce excess ACTH are very rare. They may be found in the lung and can be carcinoid tumours. The excessive production of ACTH from a non-pituitary tumour is often termed ‘ectopic ACTH production’ (ectopic meaning 'from the wrong place' – i.e. not from the pituitary gland). The source of the excess ACTH may not be immediately clear.

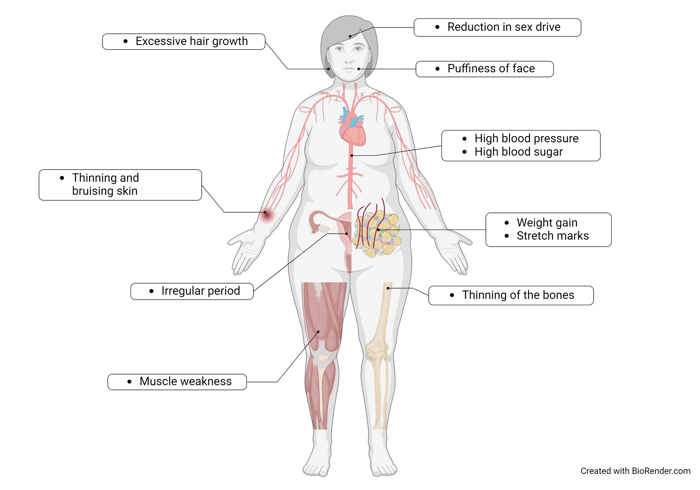

What are the signs and symptoms of Cushing’s syndrome?

Cushing’s syndrome is characterised by the following signs and symptoms:

- central weight gain(fat deposition around the chest or the abdominal region but thin arms and legs)

- a moon-like face (rounder and redder than usual)

- fat deposition above the collar bone and behind the neck

- thin skin that bruises easily

- muscle weakness, especially of the shoulder and thighs

- high blood pressure

- high blood sugar level (glucose intolerance or diabetes mellitus)

- stomach ulcers

- thin bones (osteoporosis) and increased risk of fractures

- increased rates of infection and poor wound healing

- depression and other psychiatric problems

- excess hair growth and irregular periods in women

- reduced libido and erectile dysfunction in men.

How common is Cushing’s syndrome?

The most common form of Cushing’s syndrome is the exogenous form, i.e. due to the patient taking an excess of steroid medication. Endogenous Cushing’s syndrome is rarer and is estimated to affect 1 in 500,000 adults per year. Of these, 85% have pituitary-dependent Cushing’s syndrome, 10% have adrenal Cushing’s and 5% have ectopic adrenocorticotropic hormone production (from a non-pituitary tumour).

Is Cushing’s syndrome inherited?

Cushing’s syndrome is not usually inherited, but in very rare cases can run in families.

How is Cushing’s syndrome diagnosed?

Patients with suspected Cushing’s Syndrome have diagnostic screening tests to confirm whether it is present. The clinical suspicion of Cushing’s syndrome is more accurate than any test. Before embarking on any tests, it is important to check if steroids are present in current medication the patient is taking, to rule out exogenous Cushing’s syndrome. Steroids can be found in prescription medications such as tablets, creams, ointments, inhalers, drops or sprays. Occasionally, steroids may be found as a contaminant in certain herbal preparations.

The initial screening tests are the overnight dexamethasone suppression test, the low dose dexamethasone suppression test or 24h urine collection for cortisol levels, and more recently late night salivary cortisol levels. In the suppression tests, a synthetic steroid called dexamethasone is taken late at night followed by a blood test for cortisol at 9 a.m. the next morning. In patients without Cushing’s syndrome, cortisol levels are suppressed to low levels but in patients with Cushing’s syndrome cortisol levels will remain un-suppressed. After confirmation of Cushing’s syndrome, the causes of the syndrome are differentiated by further tests.

Further blood tests include the measurement of ACTH levels (low in adrenal tumours) and the corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) and other dynamic tests may distinguish pituitary disease from ectopic ACTH. Specialised computerised tomography (CT) scans of the adrenal glands or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans of the pituitary may help determine the source of Cushing’s although false negative or positive results are possible so need an expert endocrine opinion.

Inferior petrosal sinus sampling (IPSS) may be carried out to determine whether the source of ACTH production is within the pituitary gland and to distinguish this from ectopic ACTH. This involves placing thin plastic tubes, under local anesthetic, into a vein in the groin area (the area of the hip between the stomach and the thigh). These are threaded into the blood vessels next to the pituitary gland with the aid of an X-ray machine and are used to take blood samples, after an intravenous injection of CRH. The blood samples will help distinguish Cushing’s disease from ectopic ACTH production.

A bone mineral density test may also be carried out to examine if the patient has reduced bone density and to determine the risk of developing osteoporosis (weakened and thinner bones) as well as a screening test for diabetes mellitus.

It may take some time before investigations are complete and Cushing’s syndrome is diagnosed.

How is Cushing’s syndrome treated?

Exogenous Cushing’s syndrome is treated by gradually reducing the steroid drug dose under medical supervision, whenever possible. This must be done in conjunction with the specialist who prescribed the steroid drug. In some serious conditions, the steroids cannot be stopped. For some conditions, there are alternative drugs to steroids, but these might have their own side-effects. It is very important that the patient does not stop taking any steroid medication without discussing it with their doctor.

Depending on the cause, endogenous Cushing’s syndrome is treated by surgery, medication, or radiotherapy. Patients should be treated in a specialist centre with dedicated endocrinologists and surgeons working in a multidisciplinary team. The main goals of treatment are to bring cortisol levels back to normal, to reverse signs and symptoms and to maintain control in the long term.

- Pituitary tumours may be able to be removed by surgery through the nose (‘trans-sphenoidal’) leaving no visible scars. The surgery will be performed at a specialist neurosurgical hospital and results in a 60–80% success rate depending on a number of factors. See the article on Cushing’s disease for further information.

- The adrenal glands can be removed laparoscopically (by keyhole surgery through small cuts in the skin) at a specialist hospital. For Cushing's disease, it is sometimes necessary to remove both adrenal glands if pituitary surgery cannot be performed (or is not successful) and results in hypoadrenalism, which requires life-long steroid hormone replacement. This treatment is also an option for ongoing raised cortisol in ectopic ACTH syndrome.

- Surgery to remove an adrenal gland is usually the best treatment option for adrenal Cushing’s syndrome when only one adrenal gland is affected; in this case there is usually no need for life-long steroid dependency. In cases where both adrenal glands are affected, an alternative treatment may be considered as Nelson’s syndrome (a disorder characterised by an enlargement of an ACTH-producing tumour in the pituitary gland) may develop after removal of both adrenal glands.

- Medication can be given to reduce the amount of cortisol produced by the adrenal glands. Drugs such as metyrapone or ketoconazole are given in tablet form, either for a short period to prepare patients for surgery or while awaiting the effect of radiotherapy, or for the long term if the patient is not fit for surgery. In severely ill patients where oral medication or surgery are not suitable, etomidate may be used to treat severe Cushing’s.

- Radiotherapy to the pituitary is used if surgery is not an option or has not been successful. This is an outpatient treatment and involves the patient receiving small daily doses of radiation for four to five weeks.

Are there any side-effects to the treatment?

For Cushing’s disease patients who have received a surgery, some may experience loss of sensation of smell temporarily, which usually returns to normal after a few weeks or months. Some may feel thirsty and urinate more often, a condition known as Diabetes Insipidus, which is usually temporary but can be permanent occasionally. Such condition is usually improved after prescription of a drug called desmopressin.

In addition, some may feel weaker in strength and experience mood changes due to a temporary suppression in the body’s cortisol production. To relieve these effects, it is often necessary for the patient to take hydrocortisone tablets to replace the cortisol hormone. Patients would become very unwell if this treatment is stopped without ensuring that production of cortisol has returned. Hydrocortisone tablets are taken two to three times a day until normal pituitary and adrenal function is restored. This could be for several months or patients may need to continue taking hydrocortisone for life.

If pituitary surgery or radiotherapy is carried out, the patient may develop deficiencies of other pituitary hormones (hypopituitarism), which may need replacement tablets. It may be necessary for the patient to take tablets for life to replace these essential pituitary hormones.

Tablets taken to reduce cortisol levels can have side-effects on the liver and kidneys, so regular blood tests are carried out to make sure the patient is on the correct dose and that there are no serious problems.

What are the longer-term implications of Cushing’s syndrome?

Following successful treatment of Cushing’s syndrome, it may take between several weeks and a couple of years for the changes due to excessive cortisol production to return to normal and for the symptoms to disappear. Muscle and bone strength will improve, but some patients, particularly post-menopausal women, may need treatment for osteoporosis. Blood pressure and blood sugar should be closely monitored.

Patients may need to take hydrocortisone replacement tablets for life. Higher doses of hydrocortisone must be supplied for medical emergencies as the body is unable to make its own cortisol in response to stressful situations. Patients should also carry an intramuscular hydrocortisone injection in case of emergency, a steroid card, and wear Medic-Alert jewelry.

It is important to recognise that even after treatment for Cushing’s syndrome, some patients do not regain their original quality of life, or it can take many months or years. The amount of investigations, treatment and follow-up means that genuine diagnosis of Cushing’s is very time consuming for the patient and their relatives.

Are there patient support groups for people with Cushing's syndrome?

Pituitary Foundation may be able to provide advice and support to patients and their families dealing with Cushing's syndrome.