Alternative names for prolactinoma

Lactotroph adenoma; prolactin producing adenoma

What is a prolactinoma?

The pituitary gland is the ‘master gland’ which produces multiple hormones that control the functions of many other glands in the body.

A prolactinoma is a benign (non-cancerous) tumour of the pituitary gland that produces too much of the hormone prolactin.

Prolactin is a hormone that is secreted from the pituitary gland. It has many different functions in the body including controlling pregnancy and milk production (lactation) and helps to regulate the function of the reproductive system.

According to its size, a prolactinoma can be either a microprolactinoma (smaller than 1 cm in diameter) or a macroprolactinoma (larger than 1 cm in diameter).

What are the signs and symptoms of a prolactinoma?

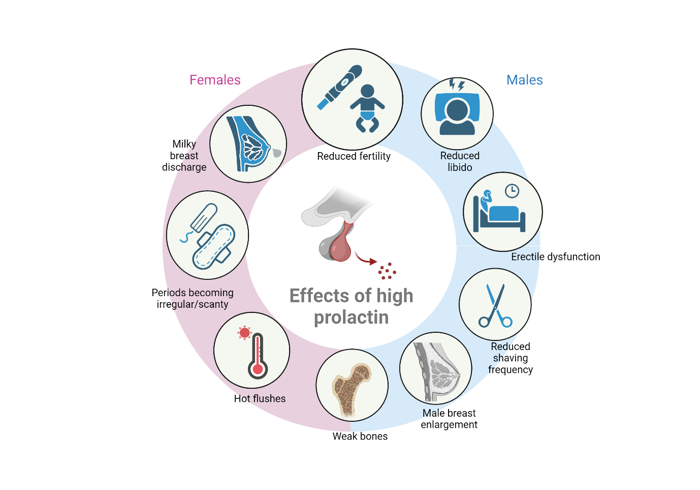

Effects of high prolactin. Made with Biorender

Symptoms of a prolactinoma relate to the high prolactin levels in the blood and includes milky discharge from the breasts (called galactorrhoea). This is more common in women than men. High prolactin can also affect the function of the ovaries or testes. In women, this can lead to irregular periods or periods stopping altogether, reduced fertility and menopausal symptoms due to low oestrogen, such as hot flushes.

In men, excess prolactin can reduce testosterone, causing decreased sex drive (libido), enlarged breasts (gynecomastia), erectile dysfunction, decreased body and facial hair.

If left untreated, low sex hormones can also lead to bone loss called osteoporosis in both men and women.

Most prolactinomas are small in size (microprolactinoma), so the tumour mass itself does not usually cause specific symptoms. Large prolactinomas (macroprolactinomas) can cause compression of the normal pituitary gland and the surrounding structures. This can impair the release of other pituitary hormones (see the article on hypopituitarism). They may also cause compression symptoms like headaches and visual disturbances.

How common are prolactinomas?

Prolactinomas are the most common form of hormone producing pituitary tumours. About 1 in 10,000 people have a prolactinoma. It can occur in both sexes and at any age, but it is more common in women aged 20–50 years. Microprolactinomas are much more common than macroprolactinomas.

Are prolactinomas inherited?

There is no evidence of inheritance in most cases of prolactinoma. Rarely, prolactinomas can occur as part of a condition called multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN Type 1), which can be inherited. Recently, several other genes such as AIP (aryl hydrocarbon interacting protein) and SDH (succinate dehydrogenase), have been described in patients with prolactinomas, and rare prolactinoma families suggest the presence of a yet unknown gene or genes in these individuals.

How is a prolactinoma diagnosed?

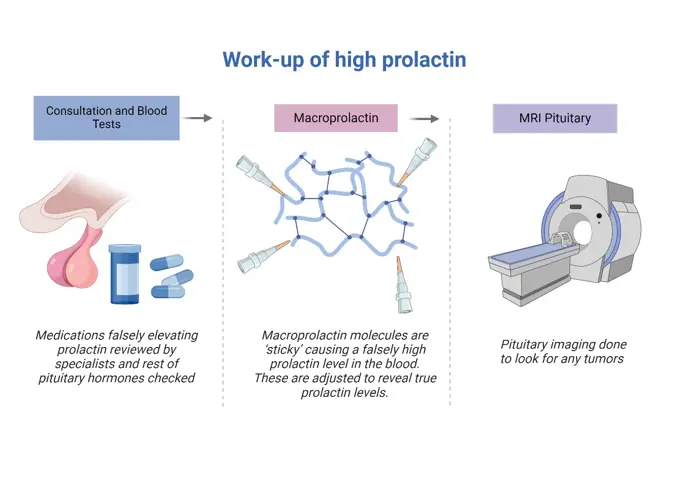

A high prolactin level in the bloodstream doesn’t always mean a prolactinoma. Pregnancy, stress or even venepuncture (blood taking) can increase prolactin. The hormone prolactin can also be increased by a number of medications, particularly those to treat anxiety and depression, and anti-sickness medications.

If a blood test shows high prolactin, it is also important to look at macroprolactin, where the prolactin molecules in the bloodstream are ‘sticky’, causing a falsely elevated prolactin level on a blood test. Macroprolactin does not cause any problems in the body, but it is important to exclude as a cause of high prolactin, as patients with macroprolactin do not need any further investigation or treatment.

Once these causes of high prolactin have been excluded, a pituitary MRI scan may be performed to study the pituitary gland and see whether there is a tumour.

How is a prolactinoma treated?

Treatment of high prolactin. Made with Biorender

A prolactinoma requires treatment only if it is causing symptoms related to high levels of prolactin in the blood level or because of its size. The aim of treatment is to normalise prolactin levels, reduce the size of large tumours and to restore normal pituitary function, thus improving quality of life.

Most prolactinomas respond well to medication in tablet form. This treatment is very effective in reducing prolactin secretion from the tumour and reducing the tumour size. Occasionally, surgery is necessary if a prolactinoma does not respond to medication or if the patient cannot tolerate the medication.

Medication used to treat prolactinomas belong to a group called ‘dopamine agonists’. The most used dopamine agonist is cabergoline which is taken one to two times a week. Other dopamine agonists include quinagolide and bromocriptine.

Dosages are titrated to prolactin levels, so regular blood tests are performed. The aim of the therapy is to achieve a normal prolactin level, ideally with a reduction in the size of the prolactinoma.

Are there any side-effects to the treatment?

Side-effects of dopamine agonists include nausea, vomiting, loss of appetite, dizziness and drowsiness. Taking the medication with food and in the evening can reduce some of these side effects.

Impulse control disorders such as compulsive shopping, compulsive eating, gambling and hypersexuality are associated with dopamine agonists. Although these are rare side effects, it is important that patients taking a dopamine agonist to treat their prolactinoma are aware of these potential side effects.

Some patients with Parkinson’s disease who are taking large doses of cabergoline develop heart valve thickening and this has led to some discussion as to whether patients with prolactinomas should have regular ‘screening’ ultrasound scans of the heart (echocardiogram). It is important to note that the doses of cabergoline used in Parkinson’s disease are much higher than those used to treat prolactinomas

What are the longer-term implications of a prolactinoma?

The outcome for patients with prolactinomas is usually excellent as the majority respond well to medication. However, they will require regular monitoring by their GP and/or an endocrinologist. As the prolactin level returns to normal the function of the ovaries and testes returns to normal, including recovery of fertility. Contraception should still be used in the normal way to prevent pregnancy. However, if conception is desired and pregnancy is confirmed, the doctor will usually ask the patient to stop taking dopamine agonist medication. A small proportion of patients (generally those with larger tumours) will need to continue with dopamine agonist therapy during pregnancy. The frequency of follow-up during pregnancy will depend on the size of the prolactinoma.

In the long-term, a proportion of patients with a prolactinoma, particularly if they have normal prolactin levels and their prolactinoma has become smaller with dopamine agonist treatment may trial discontinuing dopamine agonist treatment.

Are there patient support groups for people with a prolactinoma?

Pituitary Foundation may be able to provide advice and support to patients and their families dealing with prolactinoma.